Israeli medtech is widely regarded as world-class both by investors and the industry at large. Israeli biotech, on the other hand, does not (yet) enjoy similar standing. True, there are some notable successes on the international stage such as Protalix, Prolor and the up-and-coming BiolineRx, but on the whole, investor interest in Israeli biotech has been lukewarm at best.

The stereotype view is that strong local demand conditions led to the development of a cutting-edge defence industry which in turn laid the foundations for high-tech and then medtech start-ups, whilst biotech did not benefit from this stimulus. Whilst this is at least partly true, it does not fully explain the wide gulf between the medtech and biotech sectors.

Success to Date

Israel has a very strong talent pool, and has been acknowledged as a world leader in the quality of scientific research institutions (WEF 2010/11). It has the highest percentage of engineers in the world, as well as the highest number of physicians per capita. It is unsurprising therefore that Israel leads the world for medical device patents per capita (Source: USPTO).

Prior to 1996, Israel was home to 186 life sciences companies, but by 2010 this number had passed 1,100 (more than 34% being revenue generating), the majority in medtech or healthcare IT (Israeli Ministry of Trade, ILSI). Indeed, the medtech industry in Israel is number 3 worldwide, with many notable highlights such as:

- The Pillcam, the first miniature ingested camera developed by Given Imaging

- The closed cell stent design which facilitates blood flow to the heart by Medinol

- Surgical sealant Quixil developed by Omrix and acquired by Ethicon

- InSightec pioneered the MR guided Focused Ultrasound Surgery (MRgFUS) and is now global leader in the segment

- MediGuide, acquired by St Jude Medical, developed the Medical Positioning System, for real-time tracking of sensors mounted on devices for minimally-invasive intra-body navigation.

Medtech has clearly succeeded in start-ups, with plenty of rewarding investor exits – there has been a healthy appetite from international medical device companies for Israeli firms, including:

- Roche/Medingo

- Medtronic/Ventor

- J&J/ColBar

- J&J/Biosense Webster

- Covidien/SuperDimension

- Covidien/Oridion Systems

In pharmaceuticals, Israel can also boast impressive achievements:

- Doxil, a chemotherapy for ovarian cancer, developed at the Hadassah Medical Center and was sold to J&J;

- Teva/Weizmann Institute developed Copaxone, the multiple sclerosis treatment;

- Michael Sela, who led the group that discovered Copaxone, also led the group that discovered Erbitux;

- Azilect, a Parkinson’s Disease therapy, was developed by Teva based on research at the Technion in Haifa;

- Rebif, another MS treatment, was developed by the Weizmann Institute in conjunction with Serono’s subsidiary InterPharm;

- Exelon, a drug for the treatment of Alzheimer’s originated at the Hebrew University and was developed and marketed by Novartis.

In contrast to medtech, licensing Rx projects directly from academia to industry has proven successful.

Biotech: a Promising Start...

Israel boasted two of the earliest commercial biotechnology start-ups worldwide. InterPharm was founded in 1978 and developed recombinant cytokines for the treatment of viral infections, cancer and autoimmune diseases (IFN-β, IL-6 and soluble TNF receptors). Bio-Technology General, another Weizmann spinout, was founded in 1980 by Professor Haim Aviv. In 1988, it received marketing authorization for recombinant human growth hormone.

...But Weak Follow Through

Despite these pioneering efforts, the Israeli biotech industry did not take off in the same way that the US industry did. For more than a decade, BTG and InterPharm were the only two substantial players in the biotech sector. Both faced classic biotech problems (funding crises for BTG, regulatory delay for InterPharm).

A flurry of start-ups appeared in the 1990s, thanks largely to government incentives. The Israeli government established a steering committee for biotechnology, spawning dedicated incubators for biotechnology and a number of soft funding initiatives.

As happened in Germany at a similar time, soft money was targeted at very early stage projects producing an excess of undercapitalised companies that were little more than one person, an animal model and a patent application. Predictably, the market turned hostile to biotech, and it became extremely difficult for early- and middle-stage companies to secure funding. Some companies attempted to brave the IPO process but were treated brutally by investors who preferred the lower apparent risk and superior returns of the tech sector.

Emerging From the Shadows

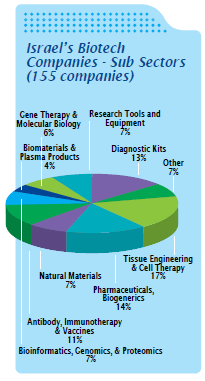

Biotech remains a poor relation to medtech in Israel, both by number of companies and by investment. Closer up, the Israeli biotech scene is actually quite vibrant (see chart).

Biotech remains a poor relation to medtech in Israel, both by number of companies and by investment. Closer up, the Israeli biotech scene is actually quite vibrant (see chart).

A number of these are still ‘one man and an animal model’ start-ups based in incubators (with onerous equity/IP hooks), some with a small amount of funding mainly from the Israeli Office of Chief Scientist, and all starved of cash. But, at the same time, there is a growing number of innovative companies with experienced management and backers. The Israeli biotech sector has particular strengths in biologics, vaccines and cell therapies. An A-Z of promising companies include:

- Andromeda Biotech, co-owned by Teva and local investor Clal, in Phase III with Irun Cohen’s pioneering peptide therapy for type 1 diabetes;

- BioLineRx, a clinical-stage, biopharmaceutical company based in Jerusalem;

- BiondVax, developing a Universal Flu Vaccine;

- CureTech, developing novel, broad-spectrum, immune modulating products for the treatment and control of cancer, with lead product comprising an anti PD-1 mAb;

- Gamida Cell, a phase III stage cell therapy company which has partnered its lead product with Teva;

- Macrocure, with its potentially revolutionary cell therapy for hard to heal wounds (already on the market in Israel);

- Protalix, harnessing its plant cell-based protein expression system for biologics;

- Proteologics, exploiting the ubiquitin system for the discovery and development of novel therapeutics, with an SAB led by Nobel laureates Hershko and Ciechanover who discovered the ubiquitin system;

- Quark Pharmaceuticals, one of the pioneers in RNAi therapies;

- Vaxil Bio Therapeutics, developing T-cell vaccines for tuberculosis and cancer;

- Pluristem, heading toward multi-national Phase II/III trials with its proprietary PLX stem cell technology;

- VBL Therapeutics, with over $100m raised and a Phase II candidate for atherosclerosis.

This non-comprehensive selection of some of the more mature companies may herald the long awaited coming of age of Israeli biotech. The corollary, we believe, is that amongst some of the nascent start-ups and one man bands are some uncut gems, some of which have strong potential that warrants serious investor attention.

Transformed by Teva?

It is too strong to attribute all of the development of Israeli biotech to Teva, but there is no doubt that this company’s impact has been increasingly influential. Teva’s rise has been dramatic: from local distributor at the turn of the 20th century, through to medicines formulator and manufacturer, into the largest global generics company and now 12th largest global pharma (Scrip 2011 league tables), positioned between BMS and Amgen. This has groomed a generation of local talent, many of whom now populate the Israeli biotech ecosystem, meeting the shortage of management talent that dogged the early years of Israeli biotech. Teva has also brought local biotechs under its umbrella to feed its nascent R&D pipeline, and has been especially active in biologics and cell therapies. This trend is likely to continue if Teva chooses to play the role of a national champion.

Back to the Future?

Looking at numerous papers and studies on this topic, it seems that every five years or so someone asks “when will Israeli biotech grow up?”. Strategy consultant Monitor Company prepared a report for the Israeli Office of the Chief Scientist in 2001 called “Realizing our Potential”. A 2006 report from the Harvard Business School focussed on the “microeconomics of competitiveness” in the sector. These, and others, highlighted the need for concerted action by all stakeholders from government to academic institutions to investors to entrepreneurs in order to create a thriving biotech cluster.

Such recommendations are fairly commonplace in dozens of similar studies and whitepapers focussed on every country/region/state/city in the world seeking to emulate the biotech success stories of the West and East Coasts of the USA. Almost none of these studies provide any meaningful value, largely because they try to discover the ‘secret sauce’ which simply does not exist.

But we believe the foundations are now in place in Israel:

- networks of local VCs, investment angels, experienced managers and entrepreneurs;

- inflow of international capital for biotech (e.g. Roche’s collaboration with Pontifax; Orbimed’s $200m dedicated Israeli fund);

- investment by Big Pharma (e.g. Merck-Serono’s new drug development incubator).

The old joke says that biotech is the industry of the future – and will probably always be. In Israel, perhaps, that future is now.

Download a PDF version:

Biotech in Israel: A Land of Promise